by Alissa Ordabai

— Columnist —

The great pianist Murray Perahia, whose management team I was a part of at one time, shared once a profound insight after a performance that could have made a believer out of a stone — his 2016 rendition of Beethoven’s Hammerklavier at Lincoln Center. He said that even the works of the greatest classical composers have had their periods of gathering dust in obscurity before the world woke up and realized what they had on their hands. And that brilliance often takes a very long time to become recognized.

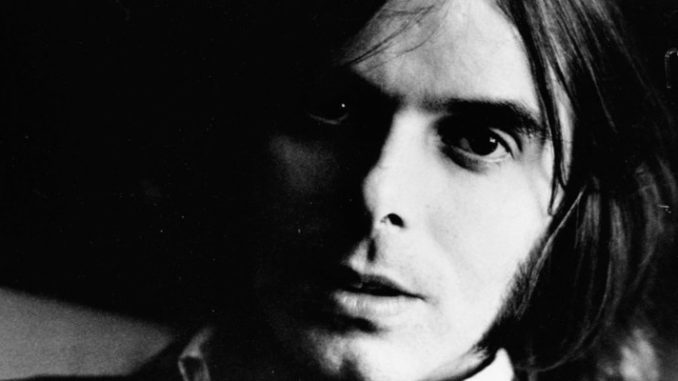

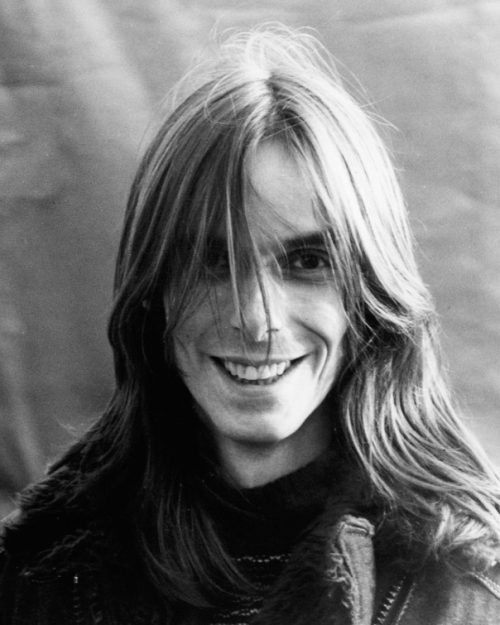

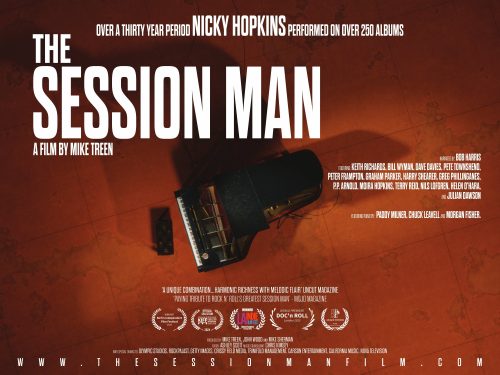

That truth came back to me when I watched Michael Treen’s recent remarkable documentary about Nicky Hopkins. A British session pianist, Hopkins didn’t just play on the biggest tracks of the ‘60s and ‘70s — he co-created them and at times defined them, smuggling the elegance of classical music into the grittiest rock ‘n’ roll. If rock ever received one true, big gift from the conservatoire, it was him.

The contrast between his profound influence and his relative anonymity makes Hopkins a fascinating figure, and Treen’s film lands at just the right moment, when the demand for historical truth locks arms with advancements in tech.

Thanks to AI, we can now, after decades, finally properly hear Hopkins’ piano parts after they remained buried in the mixes under layers of guitars on dozens of classic records. Go on YouTube and you will find Nicky Hopkins’ isolated tracks raw and bare — whether on Lennon’s Imagine or the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street — showing how transformative he was to those albums, not as an auxiliary, but as an integral part. How he could make his piano both whisper and roar, slip into background and yet be the pulse of the whole thing.

And the historical truth is not only that Hopkins has played on over 300 albums in his lifetime spanning iconic bands such as the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, John Lennon, the Who, and the Kinks, and extending into the 1980s with collaborations alongside Joe Satriani and Izzy Stradlin. But that quantity was matched by quality — consistent work of great finesse and artistry which transcends genres and trends.

Listen to his piano on the Stones’ “She is a Rainbow” and you will instantly hear an artist who fuses brilliance with vulnerability, playfulness with depth. That lineage of English eccentricity he represents — charming, unassuming, yet deeply compelling gave him the cultural tools, but he wielded them in a way no one else did with his humanity and that rare quality that many “greats” lacked: the ability to inspire awe without pretense.

Treen, the man behind the lens, deserves his due for walking the volatile terrain of corporate rock with care of a true diplomat guarding Hopkins’ legacy. Pulling in voices such as Keith Richards, Pete Townsend, and Dave Davies came at a cost — there are gaps in the narrative, hushed tales left in the shadows. But rest assured, all of this will be unearthed by future researchers.

Because it hasn’t been an easy life. Hopkins suffered from Crohn’s disease, a condition that gnawed at him, slowing him down with the music wanted to run. But the industry, for all its glitz, wasn’t kind either: it dealt him both subtle roadblocks and outright insults. Six pounds and ten shillings for “Revolution” with the Beatles. Nothing for touring with Jeff Beck in the late 1960s. (“He still never paid me,” Hopkins told NME in 1974). Limited public recognition and a lack of spotlight from the bands he elevated. And worse still, his contributions — those vital piano parts — were often plunged so deep in the mix that they were robbed of the brilliance they deserved to truly shine.

“You can feel them but you can’t hear them,” Hopkins said with a touch of quiet frustration of his piano tracks on classic rock albums in an interview to Peter Rodman shortly before his death in 1994. “I feel my piano should be way up in the mix.” And he was right, because the industry time and again turned his brilliance into wallpaper.

Now, technology is fixing what people wouldn’t. You can go on YouTube and pull his work from the shadows and listen — really listen. Tracks like “Angie,” “Let It Loose,” and “Jealous Guy” hit differently when you realize how much they owe to him. Hopkins poured a rare kind of vulnerability into rock ‘n’ roll — exposed, unguarded, yet paired with phenomenal technique and erudition. Few artists manage that balance, and let’s face it, most don’t even try. But Hopkins? He didn’t just try — he nailed it.

Treen’s film captures Nicky’s magic, but it doesn’t pretend to have all the answers. It doesn’t dig too deeply into the ugliness of the industry or the pain of his personal struggles. That’s a job for another time, for other storytellers. Instead, the documentary feels like an invitation — to know Hopkins, to honor him, to start the conversation.

And it’s a necessary conversation. Nicky’s story is filled with unanswered questions, unrealized potential, unfinished dreams, and the tragedy of an untimely loss. Hunter S. Thompson’s words about the music business being “a cruel and shallow money trench, where thieves and pimps run free, and good men die like dogs” ring all true here.

The film — made with so much love and care — leaves you with a lingering sense of mystery and tragedy to Hopkins’ life, a feeling of loss not only of a great, unrepeatable musician, but an embodiment of what once was most fragile and adorable in the English character — quirkiness, sincerity, and deep inner attunement to the mystery of life.

Hopkins’s tale is a cautionary one, but the caution in it is for the industry — to stop exploiting the people who give your machine its heart. It’s not just about recognition or applause; it’s about paying up and showing respect while musicians are still alive to feel it. Because Nicky Hopkins was certainly one man who deserved more from the world he gave so much beauty to.

The “what ifs” surrounding Nicky — the life he might have led, the music he might have created, the joy he might have experienced — add a layer of poignancy to Treen’s tale. Loving Nicky is not just about who he was but also about the dreams and possibilities that remain suspended in time.

And, finally, let me offer a word to those who work in the music trade: Nicky Hopkins’ legacy isn’t going to rise from the ashes on its own, like a phoenix fueled by good intentions. It will take effort – consistent advocacy and serious care to preserve what he left us. And maybe, just maybe, a cultural shift that stops rewarding flash over substance. Hopkins’ brilliance was always there, waiting to be seen. Now, it’s up to us not only to look, but to champion. Let us not just nod along and say, “Yeah, he was great.” Let us do things to make sure the world doesn’t forget the unassuming genius who made it all sound better.

And now the final plea. Mark Fogarty, in his book Phantom Engineer, drops a tantalizing gem about Hopkins: “In between takes Nicky would improvise piano sonatas to amuse himself, while the engineers cursed themselves for not hitting the ‘record’ button.”

So here’s the deal: if you’re one of those engineers, or you know someone who had the good sense (or dumb luck) to actually press the button, Hardrock Haven would love to hear from you. Dig through your archives, your basements, your long-forgotten reels. Somewhere out there, maybe, just maybe, lies the sound of Nicky Hopkins in his purest form. Let’s hear it.

Hardrock Haven rating:  (10 / 10)

(10 / 10)

Links:

Watch The Session Man: Nicky Hopkins on Amazon US: https://www.amazon.com/gp/video/detail/B0DBPKT9K7/

Nicky Hopkins biography by Julian Dawson: https://shorturl.at/MgFVC

Nicky Hopkins official website: https://www.nickyhopkins.com/

Alissa Ordabai studied Art History at the Courtauld Institute of Art and Sound Engineering at the Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts before graduating with a law degree from the University of London. She freelanced as journalist and editor in London from 2006 to 2014, conducting in-depth interviews with artists ranging from Alan Parsons to Aerosmith. After moving to New York in 2015 worked in classical music management at IMG Artists and in music law at Serling Rooks. She is currently Editor-in-Chief of Soviet History Lessons magazine which focuses on security, human rights, and foreign policy in the former Eastern Bloc.

Be the first to comment