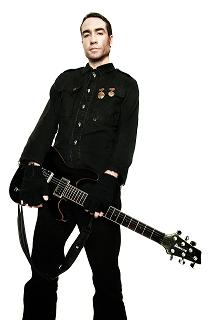

Jim Davies of Prodigy and Pitchshifter

by Alissa Ordabai

Staff Writer

An instrumental guitar record which doesn’t show off chops but introduces a new concept is something we haven’t heard since Jeff Beck’s latest studio album. This time around the revelation comes from the same side of the Atlantic in the shape of Jim Davies’s “Electronic Guitar” to be released by Mascot Records on April 20.

An album as intriguing as it is innovative, “Electronic Guitar” combines rock licks and electronic grooves to a dazzling result, boasting well-honed expertise drawn from rock and dance worlds in equal measure. Davies, of course, has perfect cred in both camps. What began for him in the Eighties with teenage studies of Steve Vai and Paul Gilbert, he was soon able to channel into electronica, making a quantum leap in his approach in mid-Nineties, which landed him playing with the Prodigy and contributing the vital guitar element to the iconic band’s signature sound.

Having come to global attention as Prodigy’s touring guitarist and playing on such anthems as “Firestarter” and “Breathe,” Davies is still best-known for his time in Pitchshifter. The golden children of British industrial rose to international fame when Davies joined them to devise a new sonic paradigm by crossing drum and bass with metal on the band’s seminal 1998 album “www.pitchshifter.com”.

Never the one to settle into an easy groove, after quitting Pitchshifter Davies continues to run a number of projects, Victory Pill being probably better known than others – an industrial outfit which boasts tunes as catchy as they are hard-hitting.

Having now decided to move into the instrumental guitar direction, Davies makes the format serve him perfectly, exploring the territory between rock and dance music with complete clarity and focus.

Taking a radically different angle from Jeff Beck’s 2003 record, Davies tackles the issue of rock and electronica interaction sonically by morphing his guitar sound into countless imitations of the synth, but still somehow manages to take it all back to rock fundamentals almost every time after romping through a tight flow of propulsive beats, quirky sounds and spaced-out guitar swirls.

While Jeff Beck’s guitar and electronic beats circle in and out of each other observing a respectful distance, Davies’s playing gets up close and personal with his dance grooves, at times uniting with them in a pulsating, thumping clinch, at times – trading high-voltage jolts in heated counterpoint crossfire.

But it doesn’t end here. Melody is as important to this album as the rhythm and the sound, Davies showing that invention of new methods doesn’t always mean that you have to deny your listeners the pleasure of a blistering rave-up or a slow, tuneful glow-in-the-dark melody. The best thing about “Electronic Guitar” is that here Davies proves that creative candour and experimentation can co-exist on one finely wrought barnburner of a record.

HRH: Jim, thank you for taking time to do this interview with us.

HRH: Jim, thank you for taking time to do this interview with us.

Jim Davies: No problem.

HRH: And congratulations on the release of the new album.

JD: Thank you very much.

HRH: Are you happy with the way this record has turned out?

JD: Yes, definitely! It’s a long story, really. I’ve always wanted to do an instrumental guitar album, but I had to find the right angle for it because there are so many guitarists out there who can deliver that sort of very fast impressive shred type of guitar playing – Steve Vai and Joe Satriani, stuff like that. And that is really not my style so much.

I didn’t want to do an overly technical guitar album, but at the same time I wanted to do something in my style which has always been quite weird sort of guitar sounds. So the angle was to do a guitar album where literally all the sounds apart from the drums and the bass would be created on the guitar.

So there is no synthesisers, there is nothing apart from guitar sounds. So I’m really happy with it. This is something that I always wanted to do but, like I say, I didn’t want to do a normal guitar album because I don’t think Mascot Records would be interested in that because they have so many fantastic guitarists, and another fast guitar album probably wouldn’t have interested them. I think what interested them about this album was that it was a bit different. So hopefully I’ve done the job.

HRH: Were you surprised that it was a rock label that released this record, not a dance label?

JD: Not really. I can understand what you mean. When I sent it to Mascot I was thinking it was a little bit too… not too electronic, but I wasn’t sure they’d like it. But it is quite rocky in places. My thing has always been electronic music and playing guitar over electronic music, that’s just turned into my style. Yes, it’s a funny one. I’m glad it was a rock label because it makes more sense. So I was surprised, but pleasantly surprised. I think things have crossed over enough for the people who are into rock music to be interested in something that is a little bit different with a slightly different flavour to it.

HRH: It sounds that this album wasn’t just an experiment in sonic boundaries of the guitar, but also an exercise of your composition skills too. I’m not saying “songwriting skills” because those aren’t actual songs, but I thought I could hear you move into a more melodic direction as the album went on.

JD: It was half and half. It was me trying to do something different guitar-wise, something that would move things on a little bit from that standard lead guitar instrumental. But at the same time you are right, because when I write songs, I write them instrumentally first. I don’t do vocals until I have written the actual music. It wasn’t much different, but the difference was that I had to make it interesting with no vocals.

I wasn’t writing a tune to show off and impress people. I was interested in writing a catchy melodic song that you’d be interested in even if you don’t play guitar. And with certain songs on the album I would have felt stupid playing fast all over. I just wanted to be quite restrained with it and write some nice bits of music but, as you said, pushing the boundaries a little bit sonically. And that was the hardest thing.

When you listen to a lot of instrumental guitar albums, they don’t pay much attention sometimes, I think, to the backing music. The backing music is almost secondary to what’s being played on the guitar. It’s almost like an excuse to… Lead guitarists only get thirty seconds in a song, but now we’ve got our own record, so we are going to do a five-minute solo on every song. That wasn’t the idea. It was trying to write some nice bits of music.

You are right, I’ve always been into trying to write melodies and that’s what interests me – trying to write catchy bits of music without vocals. It’s not easy, but… And also, I’ve played in lots of heavy bands in the past, so it was nice to… I listen to a lot of styles of music. I like funk, I like jazz, I like drum and bass, I like metal, and that all sort of makes up my guitar playing, I suppose.

HRH: Would you say that the writing process was similar to what you were doing with Victory Pill? You once said that you writing process for Victory Pill was getting the instrumental structure of the piece first and then adding the vocals as the final step. Did you have to think differently this time around, knowing that there won’t be any vocals added so you’d have to make up for that instrumentally?

JD: Yes. It’s interesting because the idea for making this album came from a B-side Victory Pill song called “Vital Signs”. It was an instrumental track. When we mixed it, I realised that all the sounds were guitar. Not intentionally, I think my synth was broken… I didn’t use anything but the guitar to make that tune apart from, obviously, the bass and the drums. And that gave an idea that I could maybe do a whole album like this. So I write it in a similar way to Victory Pill songs, in a sense that I want it to be catchy, anthemic, hooky, the usual things that would keep people interested, but at the same time I was obviously thinking, “OK, there is no vocals, so when I get to the chorus it’s gotta take off.” So I would work on the key changes and musical things like that to make it sound interesting. It wasn’t just the flat line of music and lots of guitar on top. I wanted it to move and go up and down, breathe a little bit.

Yes, it was different, but not majorly different because I’ve always written instrumental music and the challenge this time was to write it only using the guitar sounds. That was the challenge, whereas with Victory Pill we wrote some instrumental music with loads of synths, samples and stuff.

HRH: Talking about “Vital Signs”, to me it sounded like it had echoes of the Alan Parsons Project.

JD: Really?

HRH: To me it did. This electronic pulse in the background, and the way the melody is written, the way it’s really crafted, and that really spare, poignant electronic vibe it is set over.

JD: Yeah. You know what, a few people have mentioned that to me, but I’ve never heard the Alan Parson’s Project. I must listen to it.

HRH: You never heard the Alan Parson’s Project?

JD: I’ve heard of the name, but I’ve never ever heard the music.

HRH: Some other tracks on the album, like “Trip”, for example, clearly go back to that Eighties New Wave electronic music vibe. Are you nostalgic about that time? Does it have any personal significance to you?

JD: Yes, I’m massively nostalgic about that. My favourite bands are Depeche Mode and the Cure. If you said to me, “You’d never be able to listen to any music ever again but you can have your Cure albums and you can have your Depeche Mode albums,” I’d be happy. I’d be fine. That’s the big influence.

I got into those bands very late. I wasn’t there in the Eighties when this was going on. I was there maybe in the metal sense, but I wasn’t there for the electronic music. I didn’t get into it until much, much later. And I think the first time I heard Depeche Mode and the Cure I was like, “Argh” (Laughs) but I’m massively nostalgic about it now. I love the way Robert Smith’s got such a… The way his guitar sounds is very… I don’t know, just anthemic, dreamy, and it was a big influence on me, massive influence.

So yeah, there are lots of different tunes on this album that point to different things that I like. That wasn’t intentional. When I listen back to it, I go, “Oh yeah, there’s a little bit of funk and jazz in there, there is a bit from the Eighties electronica going on in terms of the guitar sound.”

HRH: Was there a concept behind this record or did it all take shape spontaneously as you went along?

JD: From doing “Vital Signs” I went to thinking, “Hang on, I think I can do a whole album of this.” If you had to show to someone who’s never heard you play guitar, what you sound like, you’re gonna give them this album and that’s gonna sum you up. There are tracks on there like “Empire” which is quite moody, slow and quite dark, and there are other tunes on there like “Hot Shot” which is a bit more funky and makes you smile, hopefully, and there are songs on there that are quite… almost hip-hop flavoured.

It wasn’t so much of a concept, but when I look back at it, it does sort of sum up what I like musically. I had to strike a balance. This is predominantly a guitar album, so I had to make sure that he beats and stuff like that weren’t becoming more important than the guitar, so I had to find a nice balance. There wasn’t really a concept, but looking back at it I suppose there is, unintentionally. I wanted to put “Vital Signs” on there because that tune was done two or three years ago and that was the very first tune that I had. It wasn’t meant to be on this album, but I like the idea of putting it on because it was the one that has kicked off the idea for it.

HRH: Let me ask you something else. Dance beats have proven to be such a great platform for conveying pretty brutal rock messages – the way Ministry and the way Rob Zombie have both done it. What is it, do you think, about rock licks set over dance beats that gives them this added gravity, this added power, this conviction, and sometimes this sinister quality?

JD: Definitely. That’s something I have to have when I write music.

HRH: But how does that work?

JD: I know what you mean. I think it’s the added power that you get from having that sort of… For me, playing in Pitchshifter for all these years, and then the Prodigy, when I was doing that, when you come off stage playing with those guys and then go to play with a four-piece punk band, it just won’t work for me. I’d just feel like it would sound so empty. And I think that’s why the music’s crossed over to the extent that it has.

There was a time when I was one of those guitarists who didn’t like dance music. I thought it was rubbish, some crap that you hear in the charts. And obviously then it changed and I got into the industrial side of things. For me it was so much more powerful. You can’t get that power from just having an acoustic drum kit.

My thing has always been… I get bored of playing rock guitar. I practiced five-six hours a day for god knows how long and so I thought, “OK, I’m not a bad metal guitarist, but what’s the point? There are ten million metal guitarists and they are bound to be better than me, so how am I going to do something different?” And that’s when I started opening my mind and getting into dance music. And that changed how I played.

I tried to emulate the sort of sound and textures you get in dance music and approached the guitar from that point of view. So for me it’s the second nature to play over dance music. It would be much harder for me to be in a normal four-piece band. I’d feel completely naked for what I want to do. This is something that shaped my sort of style, really – the sounds I use, even down to what I play.

Sometimes you can play over a dance record and there are only certain things that you can do. Take, for instance, “Firestarter”. When I played on that, the only thing that I could have played that was going to cut through that massive barrage of bass. You can’t play anything lower because you just aren’t going to hear it. So it makes you play higher squealy stuff (Laughs) to cut through. It does change how you play.

HRH: Did you enjoy Jeff Beck’s recent album where he incorporated electronica into his playing?

JD: You are not going to believe me at all, but some guy had hit me up on MySpace and said, “Really looking forward to your new album, I’m hoping it’s going to sound a little bit like Jeff Beck’s…” I can’t remember what it was called.

HRH: It’s called “Jeff”.

JD: Is it?

HRH: Yes.

JD: Right, he said, “I hope it’s gonna sound a bit like this.” I can honestly say I’ve never heard any Jeff Beck. I’ve got to go and listen to Jeff Beck and the Alan Parson’s Project.

HRH: Who were your guitar heroes when you were growing up?

JD: Hendrix, obviously. You have to. There is no way around it. You can’t be a guitarist and not like Hendrix. I love the effects that Hendrix used. That’s what a lot of people miss. His pedals and the sounds that he was doing in the Sixties.

HRH: He made a lot of those pedals himself, didn’t he?

JD: Exactly. So I love Hendrix, I always had a soft spot of Steve Vai because I think his “Passion and Warfare” was just the best instrumental guitar album ever. I don’t think there’ll ever be one as good as that again. And what, again, people forget about Steve Vai is the amount of sounds and effects he uses. Everyone concentrates on his lead guitar parts because, obviously, they are amazing, but when you sit and listen to “Passion and Warfare” with headphones on, and listen to all the textures and the sounds and the background, he’s an AMAZING composer. People forget that. He’s not just one of those guitarists who plays really fast. He’s untouchable. I do look at him and go, “I will never ever get anywhere near that.”

HRH: Do you rate him over Satch?

JD: Yeah. I love Satch, but I think he’s a bit more of a straightforward rock’n’roll guitarist.

HRH: He’s a melody guy, isn’t he?

JD: Yeah, he’s a kind of straightforward rock’n’roll guy, a bread-and-butter sort of player, while Vai is just way out there. Completely out there. And another cool thing is that I’ve always massively been into Paul Gilbert.

HRH: Really?

JD: Yeah.

HRH: He’s not much of a songwriter, is he?

JD: I don’t know. No, he did write some stuff. I think he did write quite a lot of Mr. Big stuff. I wasn’t particularly into that, but when I started playing I had all his videos, his tuition videos. “Intense Rock I”, “Intense Rock II”, those to me were like the holy grail. I remember the local guitar hero at school passed me the video, and it was really like, “Wow, he’s given me the Paul Gilbert video!” I just remember wearing out those videos, I remember going to see Mr. Big and standing outside the theatre waiting for Gilbert to come out. I remember him being very nice and saying hello.

HRH: He really is very nice.

JD: I’ve always been into his stuff. And then he disappeared for a bit and now he’s back and I just think he’s an amazing teacher. And he’s always been an amazing guitarist. You look at someone like Steve Vai and think, “I don’t think I could ever be like that, he’s just so amazing and so out there.” But then you get someone like Paul Gilbert who makes it all seem… He’s so much more… I mean, Steve Vai is a lovely person as well, but Paul Gilbert looks so approachable and you can imagine that if you put in enough time, you could be as good as that.

HRH: That’s what he tells people essentially, yes.

JD: Yeah. And what a lot of people don’t realise is that just because you are a great guitarist, that doesn’t mean you are a good teacher. Some people have a really hard time explaining what they are doing because to them it’s so natural. Some of the best guitarists in the world are rubbish teachers.

So Paul Gilbert to me is a real inspiration. I don’t like everything he’s ever done but I’ve got all his videos. He’s on the same label now as me, so that’s pretty amazing for me, that’s a real sense of achievement, that. And then again, we are very different guitarists, but I’d love to know what he thought of it. I’d love to know if he liked the album. If he didn’t like it, I’ll cry. (Laughs).

HRH: Did you challenge yourself technically on any of the tracks? Did any of them require special preparation or really intense practice before you went in to record them?

JD: Yeah, there were some parts that I did have to do over and over again. It was a tricky thing because fifty per cent of this album or maybe more was trying to create interesting sounds for the guitar without using the synthesiser, and the other half was to create nice melodies, but at the same time I wanted there to be a little bit of technical playing in there. And there is.

Some of the parts were tricky, I did have to up my game a little bit. But, like I said to you before, my foundation as a guitarist is in… When I was growing up I was learning Paul Gilbert and Vai and stuff like that. In Pitchshifter I was playing some tricky stuff, but not really that tricky.

When you are on tour for eight years and you are playing the same songs and you are up on stage, you don’t really getting any better, are you, on your instrument. When I came off tour I just said to myself, “I really need to practice a little bit more.” And this album gave me the will to do that.

But at the same time there is absolutely no point in doing a shred guitar album when you are on the same label as Paul Gilbert. Leave it to him, he’s the master.

I had to approach this and just forget about what anyone else was doing. Like, “What would you do if you did an instrumental guitar album?” I listened to some other people’s instrumental guitar albums and I didn’t like the backing tracks that sounded like an excuse for the guitarist to go, “Oh, normally I get thirty seconds to solo, now I got five minutes! I’m gonna just shred for five minutes!” And it sounds like that. And the backing track is so boring.

I always test things on my brother. He is not a guitarist, but, for instance, he likes “Passion and Warfare”, so I test things on him like a guinea pig. If he had to sit through a Paul Gilbert album, it would bore him because he is not a guitarist, but I wanted to write something that he would listen to as a non-guitarist and go, “Oh, I like that, that’s a good tune.” But at the same time, I had other tunes on the album that are a little more technical.

I’m writing the second album at the moment. I’m about eight tunes into it. This has given me a whole new lease of life in a sense. I’ve done a lot of band stuff and I sort of got to the point, “Where do I go now with bands?” I’ve had a great time and been everywhere I wanted to go, but I’m thinking, “What do I do now? Do I just keep trying to do bands? I don’t really want to do that.” So to me this has been a chance to make a path for myself as an instrumental guitarist. The fact that Mascot liked it and decided to put it out got me really excited. That was really inspiring.

I’m about eight tunes into the second one. I’ve definitely upped the game from the technical point of view as well, but at the same time keeping it like on the first album with the strange sounds.

HRH: Are you planning to continue with Victory Pill?

JD: Yeah, definitely! I’ve got about seven or eight tunes for that, it’s all coming together nicely. It’s a nice little thing. This is something that I do not for fun but there is no pressure with it. This is something that we do ourselves and we released it on our own label, and it’s not something that feels like when I was writing with Pitchshifter or something like that. There is no massive record company behind it. So it’s nice just to write music without thinking, “Oh my god, how am I going to release it?”, all that sort of thing.

HRH: You said in an interview a year ago that you felt you had little in common with the rock scene now. All the new bands sounded like Iron Maiden to you, you didn’t like any of them, and the Pitchshifter years were so much more exciting. Does it still hold true for you?

JD: It does, unfortunately. Maybe it’s because I’m getting older, but when I listen to… If I was a sixteen-year-old boy now, and I heard Bullet for My Valentine or I heard Avenged Sevenfold, all these bands, maybe I’d be really excited by it. But I think maybe because I’m slightly older and I’ve heard Machinehead, and I’ve heard Iron Maiden, and I was there with Pantera when we were doing that thing, to me it’s all the same.

I think, what I miss is when Pitchshifter was writing “www.pitchshifter.com”, it was really exciting. Has anyone done a really brutal drum and bass album? We didn’t know it at the time, but no one had, and that album still sounds pretty revolutionary to me. Those were really exciting times. Because there aren’t many rock musicians who can understand rock music and know how to do it. A lot of rock guys put a little loop at the front of their song and then something techno there, something electronic. It’s not quite like that, is it? You have to understand that it’s quite tricky, a tougher kind of music to blend into rock.

I don’t listen to any modern rock anymore. Nothing interests me from a guitar point of view. I like to listen to stuff that makes you think, “Wow, how the hell did he do that?” I remember getting the very first Rage Against the Machine album. And it was like, “Oh my god, HOW is he playing that? How is it possible?” You know? (Laughs). And when was the last time you heard an album and thought, “How did he do that?”

One thing I would say about today’s rock music is that the guitarists are aspiring to be far better players now than they used to because if they are into bands like Avenged Sevenfold or Bullet for My Valentine, they are learning hard pieces of guitar. That’s good. It’s good that they are learning technical stuff. I’d rather guitarists were learning that sort of stuff than strumming three chords and playing Oasis songs. And at the same time, I don’t know… Like I said before, all I listen to at the moment is… There is a Depeche Mode album coming out on the same day as my album, the Cure, I like Killing Joke, I like Underworld, I like Leftfield, and lots of dance music. I very rarely listen to rock anymore.

HRH: What is your take on John 5, for example?

JD: He’s an interesting guy. I haven’t heard that much of his stuff, so I don’t know. I know he likes electronic stuff.

HRH: Yes. His last release was electronic rock.

JD: Yes, it was remixes and stuff like that, wasn’t it? The American take on electronic rock is White Zombie, Ministry, Marilyn Manson, their take on it is like that, whereas the English take on it would be something like Pitchshifter, the Prodigy…

HRH: Well, basically, you.

JD: Well, I don’t know.

HRH: Because we don’t have anyone else doing that apart from you.

JD: I suppose not, no… But I don’t know. There should be. But I’ve listened to John, I think he’s an incredible player. I don’t know if I could listen to the entire album. He is, definitely, an interesting character and that’s what we need more of.