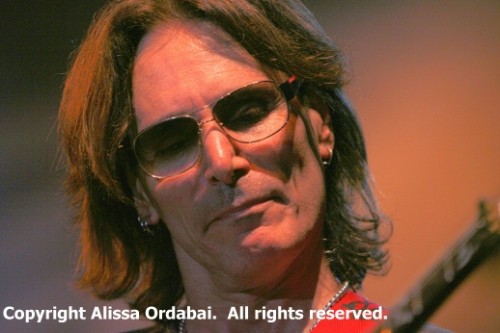

Steve Vai

by Alissa Ordabai

Staff Writer

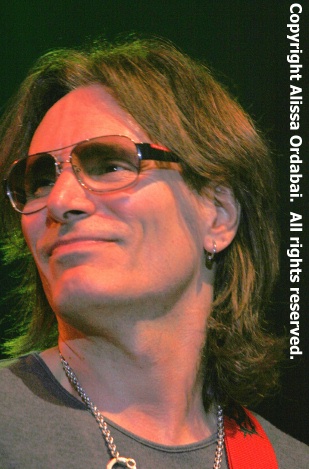

A spacious, airy room overlooking London’s river Thames gives a sprawling view of the Docklands skyscrapers and lends itself perfectly to an interview with the most futuristic guitarist of our time. Vai says that he loves London and describes it as “a truly great city”. He is here for two days (June 13 and 14) to conduct two of his “Alien Guitar Secrets” masterclasses as well as to perform on stage with Phil Hilbourne, Nicko McBrain, and Neil Murray. The two performances are a part of the London International Music Show (LIMS) and feature Vai playing three songs on each day: Hendrix’s “Little Wing”, Iron Maiden’s “The Trooper” and “Goin’ Down”.

A spacious, airy room overlooking London’s river Thames gives a sprawling view of the Docklands skyscrapers and lends itself perfectly to an interview with the most futuristic guitarist of our time. Vai says that he loves London and describes it as “a truly great city”. He is here for two days (June 13 and 14) to conduct two of his “Alien Guitar Secrets” masterclasses as well as to perform on stage with Phil Hilbourne, Nicko McBrain, and Neil Murray. The two performances are a part of the London International Music Show (LIMS) and feature Vai playing three songs on each day: Hendrix’s “Little Wing”, Iron Maiden’s “The Trooper” and “Goin’ Down”.

The venue for Vai’s two days in London is the famous ExCel Centre – a thoroughly modern glass construction with a hint of space-age futurism recently built in the heart of the redeveloped old dock complexes. It’s probably this mixture of modernity and history that London boasts these days which finds a particular resonance with Vai. After all, his own career has always been a combination of tradition and innovation, beginning with studying at the elite Berklee College of Music and later taking Vai from the confines of the convention into the direction of groundbreaking advancement.

“Artists are here so that people can dream while they are awake.” Steve Vai.

Unlike other musical pioneers who have no inclination to teach, Vai has always had a taste for sharing his knowledge with others. What began in the late Eighties with a seven-part series of columns in Guitar Player magazine, has now developed into 3-hour sessions packed with practical information, some stunning confessions, self-found discoveries and downright revelations that Vai shares with audiences ranging from 30 to 150 people, the latter being the case in London on both days in June.

“I’ve discovered that I really enjoyed speaking about the things that I have found to be important to me in my career,” Vai says during our interview a day before his London masterclasses. “Because I know that there are kids out there that love the instrument the way I did and do. There were so many great things that I’ve discovered when I was young, and even recently through my whole career. When I look back I see pivotal moments, and I like to discuss those things.”

“I’ve discovered that I really enjoyed speaking about the things that I have found to be important to me in my career,” Vai says during our interview a day before his London masterclasses. “Because I know that there are kids out there that love the instrument the way I did and do. There were so many great things that I’ve discovered when I was young, and even recently through my whole career. When I look back I see pivotal moments, and I like to discuss those things.”

During the masterclass Vai speaks persuasively and with tactful poise on general subjects such as breaking down one’s musical aspirations into bite-size goals, visualising the level of proficiency one expects to achieve, and the importance of perseverance. But he also goes in-depth on things such as ear training and specific guitar techniques.

The audience is inevitably almost one hundred per cent male with ages ranging from early teens to late 50s. At 180 pounds a pop the tickets didn’t come in cheap, but both days of London seminars have completely sold out.

As the class goes on, the ways in which Steve Vai has always been different from any other guitar player suddenly become remarkably obvious. With him it’s not only the sheer strength of his conviction and a sense of purpose he’s put into his instrument over the years but also the special kind of the love he felt for the guitar from the very start. He says he used to practice 9 hours a day when he was in his early teens. And although he gives credit to the lack of modern-day distractions such as the internet for his diligence, it still makes him sound a different breed from anyone whose attitude to the guitar has ever resembled casual.

But before you start thinking of Vai as someone whose career has been all about one enormous sacrifice, it all becomes understandable when he says, “If you are in love with it, everything else is a distraction,” delineating the difference that lies between having a hobby and being driven beyond everyday concerns.

“If you don’t know if you want to be a professional musician, if it’s an option, don’t do it,” Vai continues. “It’s a calling, it’s a gift. Everyone should play and make music. Everyone can play. But being a professional musician is something entirely different. A professional musician has no option.”

Just like his music doesn’t resemble anyone else’s, Vai’s “Alien Guitar Secrets” are as far removed from your regular rock guitar masterclass as Wright Brothers’ first flight from a space mission to Mars. With Vai, his 3-hour class is a true glimpse into the world of someone who has given his instrument all he had and in return received not only phenomenal chops, a unique ability to write, an exquisite musical ear, and fame and fortune, but also a special kind of knowledge which resides beyond the line separating chopsmen from those who are truly inspired.

Just like his music doesn’t resemble anyone else’s, Vai’s “Alien Guitar Secrets” are as far removed from your regular rock guitar masterclass as Wright Brothers’ first flight from a space mission to Mars. With Vai, his 3-hour class is a true glimpse into the world of someone who has given his instrument all he had and in return received not only phenomenal chops, a unique ability to write, an exquisite musical ear, and fame and fortune, but also a special kind of knowledge which resides beyond the line separating chopsmen from those who are truly inspired.

One such piece of knowledge Vai shares is about being able to lock with the rhythm and to groove. “Understand what it’s like to lock and to groove,” he says to his audience. “Let go, let the groove get hold of you. Listen and let it infiltrate your spirit. Meditate on it. It’s an emotional thing. Being able to lock and to groove will change your personality. It’s like everyday Christmas.”

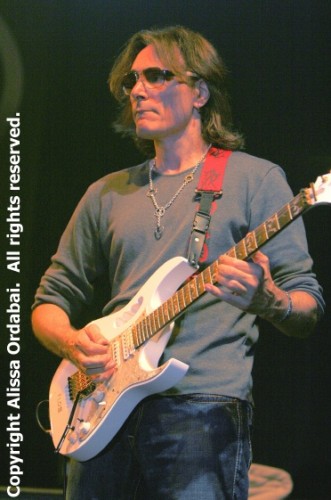

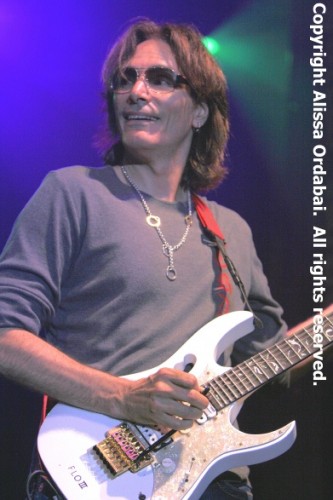

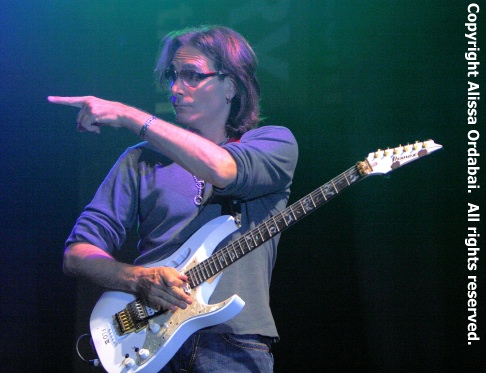

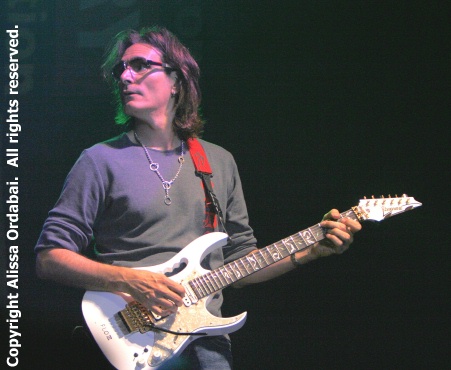

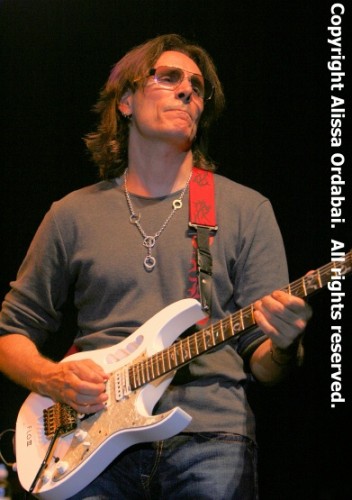

And he then immediately shows what he means by switching on a backing track and playing two completely different guitar parts on his white Ibanez Flo II. The difference is astounding – one version sounds stilted and dry, the other – an individable union with the groove, at times merging with it in a pulsating clinch, at times trading raucous bumps with it, and at times completely dissolving in it only to separate from it again for both to continue to circle in and out of each other like two high-voltage magnets.

Throughout the class Vai takes questions which range from the bizarre to the enlightened, answering all with equal patience, making a notable exception only once for a portly biker type who shouts from his seat in a thick Cockney accent: “What makes you laugh?” “Your accent,” Vai immediately fires back, chuckling, while the rest of the room breaks out into a spontaneous applause.

But he still draws the biggest applauses when he plays his music, performing several full-length compositions from his catalogue. He even takes requests, but doesn’t fulfil them all – there are some songs dating decades back that he says he would not be prepared to play simply because such a long time has passed since he last did. But despite the intensely vivid, poignant moments of hearing Vai play in such an intimate setting, the focus of the class remains on the nature of the creative process and his main emphasis on uniqueness.

Uniqueness is the concept that Vai elaborates on further during our interview when he says that challenges for guitar players vary depending on their goal. “It’s different for everybody,” he says. “One thing that I talk about the most, is being able to identify with the goal. It’s the importance of having a goal. Once you have a goal, then you have something that you are working towards. When you can visualise something, that’s the first step in achieving it. Your goal can be very simple – you just want to know how to play one song well, a Beatles song, or a Led Zeppelin song, or it could be that you want to be a completely unique elite world-class virtuoso. They all have different steps to get to them, but they are both goals. The important thing is keeping the vision of what that is and learning how to break it down into steps, and achieving each step before you go to the next one.”

Uniqueness is the concept that Vai elaborates on further during our interview when he says that challenges for guitar players vary depending on their goal. “It’s different for everybody,” he says. “One thing that I talk about the most, is being able to identify with the goal. It’s the importance of having a goal. Once you have a goal, then you have something that you are working towards. When you can visualise something, that’s the first step in achieving it. Your goal can be very simple – you just want to know how to play one song well, a Beatles song, or a Led Zeppelin song, or it could be that you want to be a completely unique elite world-class virtuoso. They all have different steps to get to them, but they are both goals. The important thing is keeping the vision of what that is and learning how to break it down into steps, and achieving each step before you go to the next one.”

Asked if there is a tension between the notion of establishing your own uniqueness and being able to go beyond the confines of the established self, being able to shape-shift between characters and personas as an artist, Vai says that there isn’t going to be a choice. “You can only be who you are,” he says. “And who we are are works in progress. We are constantly changing. Not all of us, but many of us have preconceived notions of what we should be. And the process of life is helping us to discover how to let go of those preconceived notions.”

It’s a process and I go though it constantly. Every year that goes by and I look back at what I’ve done and where I’m going and where I wanna go, I learn to let go more and more of preconceived notions, of stereotypes, of hang-ups and empty concerns. You just let go and this frees you up to find yourself more. And once you start finding yourself… Uniqueness exists in all of us because we are all different.”

“Now, if you hear somebody who plays an instrument the way that encourages you and you are inspired by it, you might learn to play just like that guy. That’s a statement of who you are. It’s not a bad thing. It just shows that you never took the desires to find out what you are interested in. And then there are people who don’t have a choice. They can’t play like anybody else, they can’t make music like anybody else.”

“Once you find out who you are, actually cultivating it and brining it out into the world is a personal statement, and a lot of people have a lot of hang-ups about that because we have these little voices in our head, and they tell us what we think we can’t do, what we shouldn’t do. We don’t want to be criticised. When you create something, it’s an expression of your inner self. If you are drawing a picture just like Picasso, it’s an expression of who you are. But if you are a Picasso, it’s different. So when we do these things, they are little snapshots of who we are. And really we are naked when we play an instrument. Because you don’t really have a choice. So when an artist takes their work and then puts it in the world and it’s open up for criticism, or for people’s enjoyment, or whatever, what happens is that they are not saying, “How do you like my song?”, or, “How do you like my art?” They are saying, “How do you like me?””

“Once you find out who you are, actually cultivating it and brining it out into the world is a personal statement, and a lot of people have a lot of hang-ups about that because we have these little voices in our head, and they tell us what we think we can’t do, what we shouldn’t do. We don’t want to be criticised. When you create something, it’s an expression of your inner self. If you are drawing a picture just like Picasso, it’s an expression of who you are. But if you are a Picasso, it’s different. So when we do these things, they are little snapshots of who we are. And really we are naked when we play an instrument. Because you don’t really have a choice. So when an artist takes their work and then puts it in the world and it’s open up for criticism, or for people’s enjoyment, or whatever, what happens is that they are not saying, “How do you like my song?”, or, “How do you like my art?” They are saying, “How do you like me?””

This accent on uniqueness doesn’t mean, however, that Vai denies his influences. During the class he names a few: Led Zeppelin, Queen, Ritchie Blackmore, Jethro Tull, and Jimi Hendrix. Talking of Hendrix, it was Vai’s rendition of “Little Wing” that became the focal point of his performances on both days at LIMS. The contrast between the poetic, transparent solos, and the poignantly outlined harmonic shape of the song, Vai’s impeccable handling of the dynamic nuances, his tone, and unpretentious grace of his performance all spoke of a seemingly innate understanding of both the original and what is required to become its successful interpreter.

Back at the masterclass, Vai demolishes the assumption anyone who’s ever heard him play live may have – that he was born great and musically perfectly formed. He admits of being insecure about his abilities when he was a teenager and says that it was hard labour that got him where he is now. “I never thought I was good enough when I was a kid,” Vai confesses to his masterclass. “I thought everybody else was better than me.” And then an even more stunning revelation follows: “Most people in this room, if they put in as much time on the guitar as I did, would probably kick my ass.”

And although over the years Vai got over his childhood insecurities and learnt to deal with fame better than most rock stars, he says that huge-scale fame wouldn’t have worn comfortable on him. “Thank god I’m not as famous as Michael Jackson”, he says during the masterclass, which, uttered just a week before Jackson’s death, sounds ominously perceptive.

Vai also says that in his early days he hasn’t been looking for fame and had low expectations not only for his very first solo album “Flex-Able”, but also for the one that followed it – the renowned “Passion and Warfare”, a breakthrough gem of an album that instantly propelled him onto the 20th century guitar hero pantheon when released in 1990. In fact, he confesses that in his youth he found the idea of fame incredibly daunting. “I was paranoid about getting famous back in the “Flex-Able” days,” he says. “The idea of fame gave me anxiety.”

Feeling uneasy about fame and, unlike 99 per cent of his peers, not being desperate for a record deal, paradoxically, allowed Vai to open up to his full potential. “If you are not expecting anything, you do better stuff than when you are attached by expectations,” Vai says during his masterclass. And as he touches upon the subject, another quote comes to mind, when back in 1989 he told Musician magazine how “…artists reach into themselves when they are young and pull out some really wonderfully originality because they don’t care. They don’t have a reputation or an image to uphold.”

Feeling uneasy about fame and, unlike 99 per cent of his peers, not being desperate for a record deal, paradoxically, allowed Vai to open up to his full potential. “If you are not expecting anything, you do better stuff than when you are attached by expectations,” Vai says during his masterclass. And as he touches upon the subject, another quote comes to mind, when back in 1989 he told Musician magazine how “…artists reach into themselves when they are young and pull out some really wonderfully originality because they don’t care. They don’t have a reputation or an image to uphold.”

Since the release of Vai’s debut “Flex-Able” back in 1984 which was recorded in his home studio, the album has sold an impressive quarter of a million copies. This year the music press is celebrating the 25th anniversary of “Flex-Able” and Vai is marking the occasion with an upcoming release of the remastered version of the album which is going to include previously unreleased bonus material recorded even earlier than “Flex-Able” itself.

This, however, isn’t the only Vai release to see the light of day in 2009. Throughout the class Vai, apart from illustrating a lot of points on his guitar, he also lets us see snippets of his upcoming DVD entitled “Where The Wild Things Are” filmed live at Minneapolis in 2007.

The DVD proves to be a startling account of the technical brilliance, versatility, and emotion of Vai’s shows. A mulligan stew of styles, techniques, and approaches, this footage makes you ponder if these days Vai is expressing highbrow culture in popular terms or the other way around. Whichever it is, it’s not just about the relationship between orchestra instruments and the electric guitar, or propulsive grooves and delicate rhythmic nuances, or constantly shifting time signatures and bona fide rock barn-burning vibe. Ultimately all this is about the relationship between heart and mind, and Vai seems to have found a perfect balance for both through his open, unconservative attitude to music.

The virtuosity with which he manipulates traditional and new practices, old technical fetishes and free-thinking innovation, can all be experienced first-had in this footage, and it startles how this diversity ultimately liberates him. This is achieved as much through balance and careful structuring as through pure emotion: on the one hand Vai doesn’t dogmatise, but on the other, his show is a firmly directed trip.

While so many bands these days cannot make their own names without referring to the established figures of the past, Vai to this day manages to remain autonomous, self-sufficient and unique. He doesn’t dose his eccentricity, and that is why artistic fascination is simply everywhere during his shows – from the music itself to the way Vai performs it on the stage, to the way the stage is designed, to what he wears. And when the time comes for the call-and-response interaction between the guitar and one of the violins, it’s all stage presence galore – a classic case where visual splendour turns great music into luxury.

While so many bands these days cannot make their own names without referring to the established figures of the past, Vai to this day manages to remain autonomous, self-sufficient and unique. He doesn’t dose his eccentricity, and that is why artistic fascination is simply everywhere during his shows – from the music itself to the way Vai performs it on the stage, to the way the stage is designed, to what he wears. And when the time comes for the call-and-response interaction between the guitar and one of the violins, it’s all stage presence galore – a classic case where visual splendour turns great music into luxury.

Asked if he is happy with the way the DVD has turned out, Vai sounds unequivocally positive. “I am very happy,” he says. “It’s a great band because I have these two violin players who are just extraordinary, really great, they add this whole different dimension, you know. And I try to do things that a relatively unexpected and different than what might be considered the norm. It took finding the right people, and I really found them: Ann Marie Calhoun and Alex DePue, these tremendous players.”

“It really allowed me to take the music into a different dimension with them. It is still very intense Vai music, whatever it is. I didn’t record with them yet, but I’ve decided to do some smattering of touring, and we did a month in Europe and a month in America and it was really great. I recorded one of the shows, it took me forever to edit it and to get it done, and now it’s done and it’s coming out.”

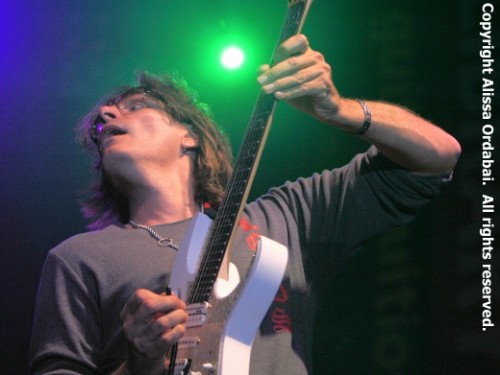

Asked what things need to coincide for a great performance to happen, Vai says that the key is confidence. “The thing that generates an effective performance is the confidence you have when you are performing,” he says. “When I’m on stage, I feel like I own the world. I am fiercely confident in what I do and I know that when I am going to do it, I am demanding that people are being sucked in. It’s a process of making a connection. Because primarily what am I here for, what are we here for? I’m here to create things for the people that are interested in it to enjoy. I’m not going to change the world, my music isn’t of historical brilliance, and if it is, it’s not for me to determine, it’s for historians to determine.”

“My job is like anybody else’s. I have certain tools and I have certain gifts, and I want to do my best to create them in the most imaginative way and powerful way that I can so that other people can enjoy them. I work for other people. Artists are here so that people can dream while they are awake. That’s what you do when you watch and it takes you away, and that’s the goal for me. I want to create something that people can enjoy and be stimulated, and I want to take control of their emotional equilibrium and bring them to different places, and let them go of the world, let go of everything in their life and just enjoy this particular thing. The only way to do that effectively for me or anybody else, I think, is to find a thing that you are most comfortable with, that’s most natural to you, that seems simple to you. That is when you are going to be your most effective. I don’t work on things I’m not good at. I find things that I am good at and I exaggerate them.”

The dynamics of performing live and composing music being different, it feels important to ask Vai about the nature of his creative process. “Well, my creative process is very simple,” he says. “I don’t think it differs from anybody else’s. The impetus of an idea has to start some place. And it doesn’t start in the physical world, it starts in the mental. You get an idea for something and you see it. You do it, we all do it. The process of making idea real in the world varies. And according to the complexity of the idea or the tools that are at your disposal, that is going to determine how much work has to go into it.”

The dynamics of performing live and composing music being different, it feels important to ask Vai about the nature of his creative process. “Well, my creative process is very simple,” he says. “I don’t think it differs from anybody else’s. The impetus of an idea has to start some place. And it doesn’t start in the physical world, it starts in the mental. You get an idea for something and you see it. You do it, we all do it. The process of making idea real in the world varies. And according to the complexity of the idea or the tools that are at your disposal, that is going to determine how much work has to go into it.”

“There are various ways to expressing those ideas. When I’m just playing the guitar, a lot of things go through my head. Sometimes I’m thinking, “What’s coming up next? Am I prepared for this? Make sure you get to your pedal in time, make sure that you look good while you are doing this.” Whatever it is. Or, “Oh my god, am I in tune?” Sometimes those are all the things that are going on, but for the most part it’s just letting go and you know that you are in control.”

The same point Vai emphasises during the masterclass, when he describes how in his early years he visualised how he wanted to look and feel on stage: “I wanted it to look elegant, effortless, complete control, no barriers,” he says. “But most of all I wanted it to be entertaining.” All, this of course, has proven to be a self-fulfilling prophecy based on Vai’s firm belief that you become what you think of yourself.

While a face-to-face masterclass may not be accessible to all for various reasons, travel and fiscal considerations being just some of them, Vai is soon planning to launch a subscription site called Vai-Tunes where subscribers would have an opportunity to get guitar advice, hear some of his previously unreleased tunes and get access to plenty of other material. Asked when he is planning to see the site up and running, Vai says that the subscriptions will take a little while.

“My plan is to move into that direction,” he says. “I have so much music that I want to get out there, but it is not necessarily suited for a particular record. So the idea is to start creating a once-a-month release of a song digitally. And the subscription will include that and a whole bunch of stuff, we are still putting it together. I was thinking of presenting an entire Alien Guitar Secrets concept in bite-size chunks of ten minutes each. And it’d be endless volumes basically, but the subscription will contain one of those also. A lot of musicians are starting to think that way. Everything’s changing.”

Being in tune with the way fans are interacted with in the internet era is just another aspect of the more universal vision that Vai has for his profession. As a result, he proved to be one of those rare Eighties artists who some twenty years ago stood for all things innovative and ultra-modern and who to this day not only continue to evolve but carry on presenting new and innovative concepts.

Being in tune with the way fans are interacted with in the internet era is just another aspect of the more universal vision that Vai has for his profession. As a result, he proved to be one of those rare Eighties artists who some twenty years ago stood for all things innovative and ultra-modern and who to this day not only continue to evolve but carry on presenting new and innovative concepts.

Vai’s most recent work which integrates orchestra instruments into a rock band scenario prompts a more general question on the secret of successfully doing so, especially given that so many artists – from Metallica to Uli Jon Roth – have recently been experimenting in this area.

“I don’t think there’s any secret,” Vai says. “There are various ways of approaching it. For someone like Metallica you hand it over entirely to an orchestrator who understands orchestra music and you get this heavy metal music that has orchestra overtones. That’s one way of doing it that has a particular effect. And it’s cool, it sounds cool. I’ve seen rock bands do that and most of the times that’s what they do. I don’t think I’ve ever heard a rock band really doing something compositional with an orchestra. Usually they take their songs and they orchestrate it for strings.”

“But it takes a person that understands rock music, and orchestration, and the limitations of an orchestra, being a composer who works with orchestras, who hears things in their head. They know if they are going to mix a flute with an oboe, what it’s gonna sound like, a contrabass with a cello or a tuba. You just imagine it and they know. And when they are creating the colours of their composition, they have all these palettes to choose from.”

“Rock musicians do the same thing, but is it a clean guitar, is it a distorted guitar, is it an acoustic? So because I work with both things, I have the ability to take an overview and mix them both in a different way. I’m not saying it’s superior, its’ just different. It is more compositional.”

“The last time I heard somebody do it to where it sounded organic to me, it was Uli Jon Roth. He does it very well. He has a very singy type of tone on the guitar, so it all works. And he just knows how to kind of like… He understands, you know? But what I do is totally different because what he does is conventional classical music.”

But, after all, Vai has always been different from anyone else. He’s never been filled with nostalgia, he’s never been frightened by the unknown, and his vitality and conviction have been total.

Some twenty years ago Vai has contributed hugely to the changing aesthetics of the Western world, but he did so almost by chance because he’s never been consciously concerned with common artistic values of his contemporaries and wasn’t interested in either upholding them or demolishing them. Instead, he’s taught everyone who cared to pay attention a more important lesson, years before he began doing his seminars – that in this day and age originality is paramount to becoming a truly great artist.

Some twenty years ago Vai has contributed hugely to the changing aesthetics of the Western world, but he did so almost by chance because he’s never been consciously concerned with common artistic values of his contemporaries and wasn’t interested in either upholding them or demolishing them. Instead, he’s taught everyone who cared to pay attention a more important lesson, years before he began doing his seminars – that in this day and age originality is paramount to becoming a truly great artist.

Vai’s ability to harness his own uniqueness and to focus on his own inclinations without conceding to changing fashions is the main reason why his music to this day remains adequate to the contemporary reality. He can cover ground from classical music to classic rock, and be able to absorb not only what preceded him, but also go into unchartered territories, but this breadth of vision is by no means an end in itself. It is simply the result of staying true to who he is and what he wants to convey as an autonomous artist while remaining an entertainer. And it’s this combination of originality and a desire to entertain, as well as the old and the new, that Vai was able to successfully formulate. In the end his efforts brought about major rethinking not only of the place and the role of modern rock guitar, but of contemporary music as a whole.

“Trends come and go,” Vai says during our interview. “There was a time when the Beatles were really out of fashion, and people wouldn’t even say they owned a Beatles record. Or Elvis. It happened to Elvis, it happened to Led Zeppelin, it happened to Beethoven. It happens to everybody because once you so identify with the particular genre or trend, and that trend gets copied and watered down and insipid because of all the people who aren’t really inspired but they are pantomiming the genius of somebody else by creating things that their imagination is capable of more or less copying. But it doesn’t have that fine spark of brilliance that the originators had. The whole genre becomes insipid and it’s time for a chance.”

“But eventually history doesn’t remember those things. History doesn’t remember the critics who tear you apart because it’s not trendy. History remembers the genres and respects those people who were pioneers.”

“Where The Wild Things Are” DVD is out on October 5, 2009.