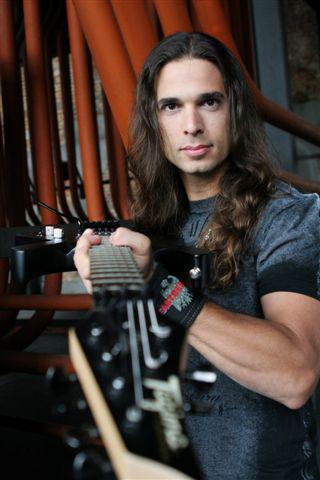

Kiko Loureiro

by Alissa Ordabai

Staff Writer

Kiko Loureiro began his career at the time when the guitar virtuoso genre was not only out of fashion, but almost defunct. The great era of rock guitar heroes who inspired Loureiro throughout his teenage years, was now over and grunge was de rigueur worldwide. The time has come for unprecedented musical austerity, major revision of trends, and deep suspicion of any guitar efforts going beyond the straightforward rhythm function. The guitar was still an instrument of self-expression, but with huge limitations imposed on it.

Kiko Loureiro began his career at the time when the guitar virtuoso genre was not only out of fashion, but almost defunct. The great era of rock guitar heroes who inspired Loureiro throughout his teenage years, was now over and grunge was de rigueur worldwide. The time has come for unprecedented musical austerity, major revision of trends, and deep suspicion of any guitar efforts going beyond the straightforward rhythm function. The guitar was still an instrument of self-expression, but with huge limitations imposed on it.

Out of this situation of severity and restriction Loureiro managed to emerge triumphant – turning his band Angra into an outfit now famous not only for its thought-provoking progressive leanings, but also for breathtakingly virtuosic guitar leads. Joining the Sao Paulo band in 1992, Loureiro never stopped developing both as a player and as a composer, releasing 8 albums with Angra, 3 solo albums, and last year – a debut record as a member of a fusion trio Neural Code.

This ability to assimilate a multitude of genres, to develop a parallel interest in jazz, and to study Latin music which he now blends so impeccably with rock, makes his latest solo album Fullblast a multi-directional, yet perfectly unified record. Full of spellbinding melodies, firework chops, and showcasing Loureiro’s phenomenal knack for mixing different genres, it is at once an accessible and a deeply personal album. Blending tradition with the feel of the new, it is the kind of record which you want to return again and again – not only to hear those magical melodies once more or to figure out the technique, but to try to understand how one can weave Latin and jazz influences into the fabric of rock so seamlessly and with such taste.

A delicately balanced, finely wrought album, it makes you wonder what lies behind this ability to balance explorative spirit with congeniality. The answer is perhaps in Loureiro’s awareness of his audience, but at the same time an innate feeling which he refers to as “sincerity” and which runs through the entire record – an ability to connect with yourself while not forgetting about your listener. This, as well as the creative process behind Fullblast and Loureiro’s current artistic priorities were the main themes of Hardrock Haven’s telephone conversation with the guitar meister last week.

Hardrock Haven: Kiko, thank you for finding time for our magazine, we really appreciate it. And congratulations on the new album!

Hardrock Haven: Kiko, thank you for finding time for our magazine, we really appreciate it. And congratulations on the new album!

Kiko Loureiro: Thank you very much!

HRH: I have to say – what an elegant, diverse piece of work! How did you manage to combine so many musical styles, and yet to produce such a coherent, unified album?

KL: I think it has to do with many years spent playing music. Playing rock, first of all, and then I am really proud of my background as a Brazilian. I really like to mix rock – things that came from England and from the United States – with the harmonies and rhythms of the Brazilian music. I studied our grooves, our rhythms, and I like to combine them to create something different.

HRH: You do it so seamlessly, it’s such a beautifully unified record. Do you have any favourite tracks on this album?

KL: I like all of them. I like the acoustic guitar tracks with Brazilian influences. This is something that I like, but, of course, electric guitar soloing is my main thing. So I like all of those songs. Each song has a different story, it came out in a different way, at a different moment, so, of course, I like all of them.

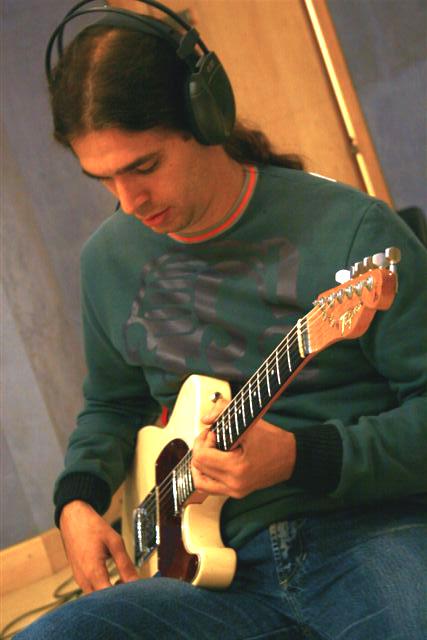

HRH: How many electric guitar solos are improvised on this record?

KL: This is instrumental music, so you have the main theme, you have the riffs, which are, of course, parts of the composition, but then you have solos which are improvised. I don’t like to study them, I just play them, I improvise the solos. I play them several times and see what I like. Sometimes it’s the first take, sometimes it takes longer, but I like to improvise.

HRH: Did you challenge yourself technically on this album? Where there any parts that you had to rehearse and go over and over before recording them in the studio?

KL: Yes. There is a song called “Cutting Edge”. On that I did a solo for the guitar freaks, the guys who like this shredding stuff. It’s quite fast, so I had to stretch for it, and I had to play sitting down and holding the guitar closer to my body, which is different to playing live, and I had to really stretch my fingers. So that was a bit technical.

HRH: How do you keep your technique in shape these days? Does it still require everyday practice?

KL: I still do it, but I don’t do that much now, to be honest. Because there are so many things that go on, and, of course, I rehearse, but I like to play a lot of acoustic guitar, and I also play other stuff, and sometimes I don’t play that much, and sometimes I play more. And then I have to go on tour, and it’s not a daily thing anymore. It used to be, of course, but now I think more about music. Going back to your other question – thinking about music is more important than technique. But there was a time in my life when I needed to work on my technique. And once I got the technique where I am now and became more secure, I began thinking about the musicality: “What can I do with the technique that I have?” So this is more important. Sometimes playing chords and chord progressions is much more fun for me than playing fast scales.

KL: I still do it, but I don’t do that much now, to be honest. Because there are so many things that go on, and, of course, I rehearse, but I like to play a lot of acoustic guitar, and I also play other stuff, and sometimes I don’t play that much, and sometimes I play more. And then I have to go on tour, and it’s not a daily thing anymore. It used to be, of course, but now I think more about music. Going back to your other question – thinking about music is more important than technique. But there was a time in my life when I needed to work on my technique. And once I got the technique where I am now and became more secure, I began thinking about the musicality: “What can I do with the technique that I have?” So this is more important. Sometimes playing chords and chord progressions is much more fun for me than playing fast scales.

HRH: Talking about composition, the album is full of such perfect melodies and such perfect phrases. Does it usually take you a long time to compose those tracks? On average – how long does it usually take you to take a track from the initial snippet of an idea to a finished piece?

KL: It’s always different. Some songs you can write in one day, and sometimes it takes longer. Sometimes you have two parts and you don’t know what to do with the other one. Whether you continue, or take a break and come back to it. But it has to be natural, the composition thing has to be natural. And composing is something that you have to practice.

HRH: It’s like a muscle that you have to exercise, isn’t it?

KL: Yes, that’s right. A brain muscle that you have to develop. It’s like speaking, putting across an idea. Some people are good at appearing in front of other people and making a speech, and some can’t communicate the message. Composition is like that. You have a melody that you like, but what are you going to do with it? If you repeat it too much, then it’s boring and the good melody is no good anymore. It has to do with the piece of music as a whole. So you have to practice. Make it so that the melody that you like is also hopefully liked by other people.

HRH: How accurately is it possible to convey the initial feeling that inspired a piece of work? Is it possible at all to convey through music 100 per cent accurately what you are feeling?

KL: Well, yes. You have to be very sincere. It’s a difficult question. You have to be very sincere about what you really like, because I think sometimes musicians are not so sincere. I think for guitar players when they do a solo album, they are not doing something very popular, you are not doing it for selling units or something like this. But you are sincere because you like that. You are not doing something because you think people will like it that way, or say to yourself: “I will not play this chord because it’s too crazy and I think people will not like that.” If you like it, you do it. When you are starting a new song, if you like it, then you will get a good feeling, you will feel it somehow. When there is something interesting going on, then there is a connection – from this melody, this chord, this song – to your body somehow. To your brain, to your body. And then you have to be sincere with that. You cannot cheat and try to be somebody else. If you compose something you like, then it’s 100 per cent. I don’t know how clear that sounds.

HRH: Very clear, or as clear as it can be when you talk about these kind of things. I have another question here, and it may sound a bit stupid, but I’ll still give it a go. Does your music ever surprise you? Do you ever listen back to stuff that you wrote, or stuff that you played, and go, “I didn’t know I had this aspect to my character,” or simply, “I didn’t know I could be like this”? Does that ever happen?

KL: Yes, yes, yes. Normally when you put some distance from your work. When you listen to something that you recorded many, many years ago. Because sometimes you are so close to the work that you are doing, you don’t get that perspective. But when I listen to some of the stuff I recorded in the 90s, I go, “Wow, that was me when I was twenty-something!”. It can surprise you: “How naïve I was, I was doing that just because of that guitar player or that music I was listening to at the time! I was not so sincere and was trying to play like somebody else!”. It happens. It surprises me when I listen to something from 20 years ago. I almost can’t recognise it. But I was studying the guitar and studying music. I’ve always been a rock guy, I was playing rock guitar a lot and listening to all the great guitar players like Jeff Beck and Steve Vai. I was trying to learn, also from acoustic guitar players, to learn interesting harmonies that took me to jazz, took me to ways of combining it with rock, took me to classical music, to some Arabian music. And I started learning how to combine rock with all those other elements. So it surprises me, the way I was doing things all those years ago.

HRH: When you were growing up, did you have a clear musical ambition or a clear musical goal?

KL: The main thing was that I wanted to play the guitar. When I was a teenager, I wanted to do it as a profession. But it was more of a teenage thing, I didn’t know what I was going to do – whether to go to the university to be a lawyer… I did biology at university. Then I began playing and traveling. I’ve always been thinking about being a musician. So I was really eager to learn music in general. To be able to play any kind of music if somebody asked me to do it. To be prepared to be a good professional musician. Then I had my band, and my band started getting more known, but I never wanted to be a rock star.

KL: The main thing was that I wanted to play the guitar. When I was a teenager, I wanted to do it as a profession. But it was more of a teenage thing, I didn’t know what I was going to do – whether to go to the university to be a lawyer… I did biology at university. Then I began playing and traveling. I’ve always been thinking about being a musician. So I was really eager to learn music in general. To be able to play any kind of music if somebody asked me to do it. To be prepared to be a good professional musician. Then I had my band, and my band started getting more known, but I never wanted to be a rock star.

HRH: Really? But you are a quintessential rock star, aren’t you?

KL: I’m not a rock star!

HRH: But of course you are!

KL: But it was not my goal. I wanted to learn about music, about this or that scale, or to understand how this guy plays, more than worrying whether my shoes were cool or not. This is what you think about when you hear the expression “rock star”. Of course, there were great musicians who were also rock stars, but I think they were more musicians than rock stars. The two can combine when you have the situation when people like their music, so they start posing for the pictures and something like that, and then you have the image of a rock star. But I wanted to grow as a musician. I want to be a better musician more than to have more people in the audience, more than having more pictures of me somewhere. I get a good feeling out of knowing that I played well on a particular night. Not from having a lot of people in the audience.

HRH: So you would be happier playing to a small club full of people who completely understand what you are doing, as opposed to a stadium of screaming fans?

KL: Yes, of course. People who like the music and are connected somehow with the music. With guitar players, the audience most of the time are guitar players as well, or they love the guitar. They know their guitar heroes and the history, and then you have this connection. But then you have to go to other places where people may not know as much about the guitar. You can play for some kids who may become interested in learning about the guitar and getting into this small club of guitar players. With the Guitar Hero thing nowadays, you can get teenagers in the audience who are there for the Guitar Hero thing, and not for the actual guitar, but then they become so interested they want to find out how a real guitar works. And I like that.

HRH: Were you ever in a position where you had to choose or compromise between making your music accessible to an as wide audience as possible, and at the same time expressing your full self? Is there a conflict between the two, or can an agreement be reached within one creative mind to balance those two urges?

KL: I don’t know exactly how to answer that because there can be a fear of something being too weird, as in, “I am playing something that I like, but maybe I am going too far?”. You can introduce some weird chords because, for example, you are listening to Frank Zappa at the time. And then you listen back to it the next day you think that maybe it’s too much. You have to have a limit and introduce people to those things step by step. I listen to some crazy, weird stuff sometimes. I mean stuff like John Coltrane. I can get into the John Coltrane thing, but if I want to produce some kind of feedback, I can’t put this John Coltrane thing into my songs, because on my album it would be too much. I like it when he uses percussion on his songs, but I can’t make it my thing and do percussion guitar, that would be too extreme. I would play rock music and then add the percussion. It’s different from the American guitar players who don’t add percussion to those grooves, but it’s not that far. Carlos Santana is a good example of how to combine Latin music with rock guitar. It’s rock with a Latin vibe. It’s not Latin music, he plays rock, and it’s a good combination. You have to show people things in a good way. Otherwise it may not work.

HRH: Do you think there is a greater degree of freedom when you do a solo album as opposed when you are working on material with a band, with Angra, for example? Do you feel more free, do you feel it’s easier?

KL: Yes. First of all because it’s a solo album. Secondly, because I’m alone. A band is a compromise with other people. You may like the song, but there are five members and they play it the way they like. If it’s a solo album, you can say, for example, to the drummer, “Please do what you want, but this is how I imagine it.” He knows it’s my album, so he respects that and he respects my vision for that music. A band is different. You have to combine the vision of five members to have one concept.

HRH: In a band situation, when do you think it’s appropriate to compromise, and when is it time to stand by your work?

KL: It’s difficult, but when you really care about the song you wrote, you can fight for that. Some songs you like, and someone can make a suggestion to change a chorus, and you agree when you like it. It can be great because you have five brains thinking. The drummer may come in and say, “We’ll do it like this – this groove instead of that,” and then you have to imagine it. He is the one for the drum grooves, not me. There are different moments, so you never know. If you are doing it alone, the entire thing is up to you. You have to believe in being right, do it the way you see it, and hope that people will like it. And if they don’t like it, it’s like, “They don’t like me.” It becomes very personal. When it’s your song, it’s like it’s you out there. If it’s something that you really enjoy, it’s like a part of you. And if someone comes along and says, “I don’t like the song,” it’s like saying, “I don’t like you.” If they say, “I don’t like the sound,” then it’s cool, it’s OK. If they talk about the sound of the album, it’s OK. But if they don’t like the song itself, if they don’t like the melody, then it can hurt. It’s complicated.

HRH: Do you think being a rock guitar player, as profession, has changed in any fundamental way since the time when you were growing up? Do you think there are more expectations now, or maybe less? In terms of technique, and being able to write, and the knowledge of theory? Do you think it’s easier now to be a rock guitarist or the opposite?

KL: I started my professional career in the beginning of the 90s. Grunge took over and it went down for the 80s guitar players. Not Satriani and Steve Vai who of course were always there, but the other ones. Guitar solos went out of fashion, and so did the 70s and the 80s stuff. There were suddenly no solos. It became more difficult for the guitar players from the 80s which was the great moment of rock guitar, and then suddenly everything stopped because of Nirvana, Pearl Jam, and all those bands. So I found my place during a difficult moment for the guitar players. Nowadays it is different again because it’s the internet era, and you have do things by yourself and take care of your career by yourself. You have to take care of your contacts, and the pictures you have to take, and your solo album, and the video you have to upload. And it’s different than 10 or 20 years ago. It’s more demanding. And the guitar complains because you play less. [Laughs]. Because you have to take care of a lot of stuff.

HRH: Are there plans to take the new record on the road?

KL: Yes. I will be playing in Italy in November. That’s it so far. Then we are going to Japan in October, and I am doing an Asian tour with Laney, the British amplifier, in October as well, and in November we are going with the trio [power fusion trio Neural Code where Loureiro plays and which released its debut album last year] as well. I have my solo gigs and the band as well, and you have to combine both agendas.

HRH: I have one last question and it’s a bit goofy. I hope you don’t’ mind, and you don’t’ have to answer it if you don’t want to. It goes like this. If you could have an answer to any question in the Universe, what would you ask?

KL: Wow! Of course it would be about the existence of god.